Calf Vein Thrombosis

When someone has a deep vein thrombosis, we treat them for three reasons: local symptoms, risk of long-term symptoms and risk of the clot moving to the lungs to cause a pulmonary embolism. But all these reasons are less for calf vein thrombosis compared to larger, more proximal, clots in the veins of the thigh or pelvis.

Calf Vein DVT: Symptoms and Diagnosis

Many calf vein DVT do not cause symptoms. But when there are symptoms, the symptoms of a clot in the calf veins are similar to the symptoms of any other deep vein thrombosis. The symptoms include sudden pain and swelling. Some people describe the symptoms as a pulled muscle. In fact, I have seen people delay diagnosis and treatment because they missed the diagnosis, thinking they had pulled a muscle.

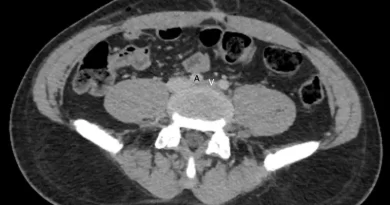

Also similar to other DVT, we make the diagnosis usually with ultrasound. The only difference is that ultrasound is less accurate for the calf veins compared to the veins of the thigh. This is especially true is there is much swelling.

A calf vein ultrasound should offer more information than just “yes/no DVT”. It should note the name of the vein with the clot. And it should also note the location of the clot in the calf. A clot that is isolated to the distal calf is not the same as an extensive clot that reaches all the way up to the popliteal vein.

A d-dimer blood test is sometimes helpful in diagnosing a DVT. It can be particularly useful to diagnose a calf vein thrombosis, especially if the ultrasound images are not clear.

Risk for Propagation and Embolization

Without treatment, some clots that start in the calves will propagate to the deep system. This extension happens in about 25-30% of cases. While we quote these figures widely, they are based on rather small studies.

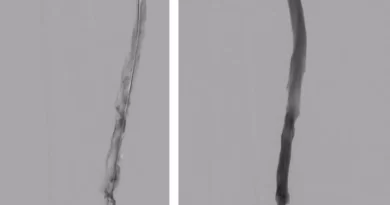

Risk for embolization (without treatment) is another concern. Obviously, some clots will detach and embolize to the lungs. For untreated proximal DVT the risk is about 40% during the first 30 days, without anticoagulation, of course. But calf clots are also important. Cadaver studies that have set the basis for our understanding of how most clots originate in the feet and calves date back to the 1930’s and early 1940’s. Later, radiographic studies repeated these findings.

But this does not answer the question of frequency. Unfortunately, the quality of data to answer this question is poor. Most studies are small. Still, in one randomized study of 259 patients with few risk factors, a composite of extension and embolization occurred in only 5-7% with or without anticoagulation. A meta-analysis reported the risk of extension at 9% and the risk of pulmonary embolism at 1.5%. Another nice summary of data can be found here.

The risk of propagation and embolization may be different depending on the location of the clot. In one study, there were more PE in patients with involvement of axial veins than in those with muscular vein clots.

Calf Vein Thrombosis Treatment

Given the relatively lower risk of severe outcomes with distal DVT compared to proximal DVT, we probably do not always have to treat with anticoagulation. So, practically, there are two options to treat calf vein clots: To treat, or to observe. In fact, guidelines support both options (see recommendations 1 and 2 here).

Observation

If we choose observation, we might offer NSAIDs for pain and warm compresses for tenderness. But we do not offer anticoagulation. Then, we repeat the ultrasound every 1-2 weeks, until we are convinced that the clot is not propagating.

Anticoagulation

The second option is to offer anticoagulation. Then, of course, the question is how long to anticoagulate for. The 2016 Chest guidelines suggest to treat for 3 months over shorter treatment. In contrast, the European Cardiology Society guidelines from 2017 allowed for shorter treatment in low-risk patients. The American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines did not specifically mention distal or calf vein thrombosis.

Choosing a Treatment Approach

So how do we choose when to anticoagulate and when just to follow? There are several considerations to take into account:

- What does the patient want to do? Often, patients will not feel comfortable with following a clot. Other times, a patient will actually refuse to take a blood thinner, but might agree to surveillance.

- How close is the clot to the deep system? There is no proven distance that we consider as “safe”. But, if a clot is within several centimeters of the popliteal vein, I would hesitate to follow and not treat.

- Are there ongoing risk factors? Think about what caused the clot in the first place. Has that reason resolved? Is it a significant reason? Can you treat it? For instance, we can sometimes get someone to move around more, but a quick fix to morbid obesity is elusive.

In practice, we may not be able to offer anticoagulation to some patients. In these patients, we may opt for serial ultrasound. Unfortunately, the outcomes of these patients may be worse than for patients who can receive anticoagulation.

Calf Vein Thrombosis and Cancer

The bottom line is that the question remains open. In theory, the outcomes of clot vein clots in cancer patients might be different than in non-cancer patients. And so maybe our approach to these clots needs to change. A study of 830 patients with calf vein thrombosis compared patients with and without cancer. Bleeding was more frequent in the cancer group, but it was hard to show benefit of treating differently. Another, smaller, study found similar results.

Pingback: IVC Filter: Definition, Indications and Complications