May Thurner Syndrome

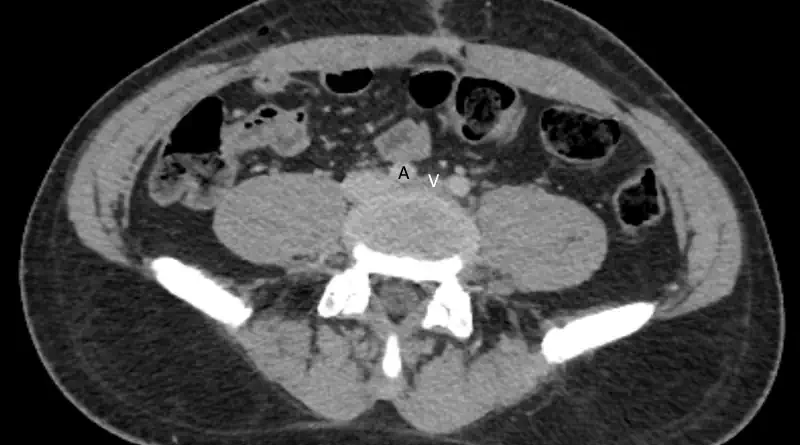

The right iliac artery goes over the left iliac vein in everyone. But sometimes, the pulsation of the artery compression the vein beneath it. When the compression is clinically significant we call it iliac vein compression syndrome or May Thurner syndrome (after the two physicians who described this in cadavers in 1957). As people are moving away from calling conditions after the people who described them, the modern term is non-thrombotic iliac vein lesion, or NIVL.

Clinical Manifestations of May Thurner Syndrome

Most commonly, we will identify compression of the iliac vein without any symptoms. Veins are pliable structures. Basically, vein walls are soft. Look at the veins on the back of your hands. You should be able to compress them very easily. Similarly, when a person lies on their back in a CT scanner, chances are that the vein will appear compressed, even if it is not. In these cases, it is just the vein wall bending inward.

But in other cases the compression is real. When this happens, then over time the vein develops scars, or spurs, in side it. These spurs can limit blood flow. The blood flow limitation might cause chronic leg swelling, varicose veins or deep vein thrombosis.

It is important to understand that DVT from May Thurner will go all the way to the iliac vein. This is because they originate from the compression. So if a patient has a DVT that is lower in the leg, even if we see iliac vein compression, that was not the cause.

Sometimes, iliac vein compression is present in people who also have renal vein compression. This combination might result in pelvic congestion or more severe pelvic and leg varicose veins.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis combines clinical signs and symptoms and imaging findings. First, regarding symptoms. It is important to distinguish related from unrelated symptoms. Not all leg swelling, leg pain or varicose veins arise from May Thurner.

When Suspect May Thurner?

We will likely suspect May Thurner more in younger patients who present with proximal and extensive DVT on the left side. This is because there are not many reasons for clots in this patient population. Of course, rarely they may have cancer, and sometimes thrombophilia testing reveals a problem. But Iliac vein compression remains an important reason to consider.

Another reason to suspect this condition is if a patient experiences anticoagulation failure. Basically, we can treat a patient with blood thinners, but if there is a severe compression then the clot will not resolve. In fact, it might even extend.

Finally, we may suspect May Thurner in people with typical symptoms, even without a blood clot in the leg. For instance, chronic left leg swelling, prominent varicose veins on the left side etc.

Imaging Studies

Assuming we suspect iliac vein compression, the next step is to prove the diagnosis. The two most useful imaging studies are CT and MRI.

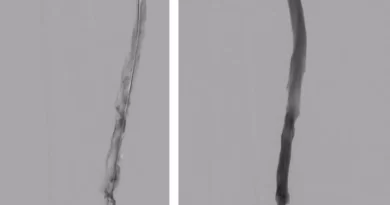

Although both tests are useful, sometimes MRI offers more information. This is because we can use a long-lasting contrast agent. Then, we can run tests to see the direction of blood flow. Basically, we are trying to see if blood needs to go around the compression through collaterals. Finding collaterals or even reversed blood flow support a real compression.

If a patient ends up having a procedure, we can use intravascular ultrasound. This tool can prove the compression from the inside of the vein. It is very useful, because it can show in real time how the artery pulsations are affecting the vein.

Having said all that, sometimes we suspect May Thurner based on ultrasound. A normal common femoral artery Doppler waveform should show phasicity. Lack of phasicity, or a flat waveform, can mean there is limitation to flow more proximally.

May Thurner Treatment

The main challenge with treatment is to decide when to treat. In my experience many patients receive unnecessary treatment for this condition. The indication to treat is not that there is compression. Rather, the indication is that there is compression accompanied by relevant symptoms.

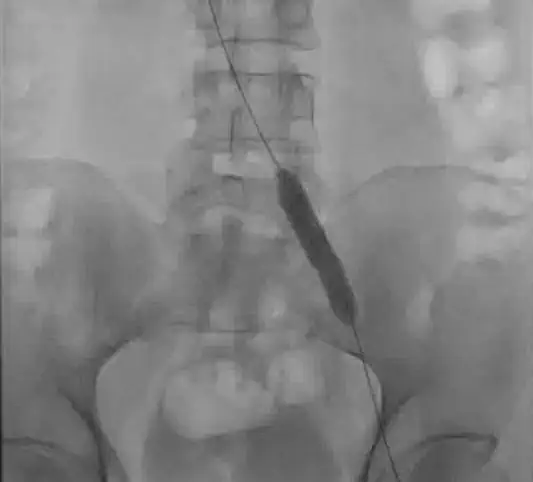

Once a decision is made to treat the compression, the main approach is endovascular. If the patient presented with an acute DVT, the first step will be to treat the DVT. Acutely, this may be with pharmacomechanical thrombolysis or with mechanical thrombectomy. But once the vein has been cleaned, the next step is to treat the compression.

To treat the compression, first, you need to prove that it is there. While venography can show compression, the gold-standard is intravascular ultrasound (IVUS). IVUS can show the compression and prove that the artery is compressing the vein. Some patient will have a different reason for compression. For instance, a tumor. So confirming the reason for the compression is important.

Next, the compression is fixed with a balloon (venoplasty). Often, a stent is placed to keep the vein open.

Medical Therapy after a Procedure

After endovascular procedures for May Thurner, there are usually two medical considerations:

First, if a patient is taking anticoagulation for a DVT, is there need to continue the treatment? The premise of this question is that the flow limitation is now fixed. So, if we assume that this is what contributed to clotting, is there any need to continue the treatment? The counter argument is that there are more people with iliac vein compression than there are people with clots. So maybe those people who developed a clot have something else wrong with them. Even if hypercoagulable testing is negative, there still may remain a risk for clotting. Unfortunately, we do not have high level data to help us with this decision.

Second, is whether patients need to take antiplatelet agents. Examples include aspirin and clopidogrel. Usually, after stent placement, we prescribe these medications, at least for a period of time. But how long is enough? Iliac vein stents are usually large, which typically means that the risk for stent failure is low. So, maybe after the first few weeks patients do not need any more medication? Similar to decisions about anticoagulation, we do not yet have high level data to help us with this decision either.

These questions are still open for discussion. At this time it seems like there is much variability in how different doctors prescribe these medications.