Pulmonary Embolism Response Team

Treating pulmonary embolism is not always simple. Of course, treating a low-risk PE is simple. Patients will only need anticoagulation. Deciding what to do with high-risk PE is also simple. Patient need aggressive treatment. But deciding what to do for some patients with intermediate-risk PE can be complicated. This is where a pulmonary embolism response team might be useful. Sometimes we use an acronym to describe these teams, PERT. The organization that is coordinating PERT internationally, is the PERT Consortium.

Pulmonary Embolism Response Team Goals

There are two separate goals for PERT. The first, is to bridge knowledge gaps. And the second is to create cohesive teams that can tackle complicated medical situations.

PERT might Compensate for Knowledge Gaps

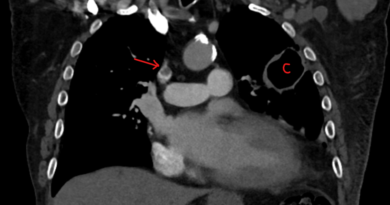

Not all pulmonary embolism are made equal. Some patients have more severe disease than others. These patients might have an enlarged right ventricle and abnormal blood tests including troponin and BNP. Of course, patient characteristics matter as well. For example, age and pre-existing conditions may make it harder for some patients to cope with a pulmonary embolism.

Most patients with intermediate-risk will do well with anticoagulation. But some patients will deteriorate. Unfortunately, identifying which patients will need extra support is not simple. Also, currently we lack the knowledge to tailor treatment for each patient accurately. This is where a pulmonary embolism response team might be helpful. In the past we relied on the clinical skill of whoever was caring for these patients to make the best decisions. But as not all doctors have the same knowledge or skill, bringing a group of team members together might prove beneficial.

Pulmonary Embolism Response Teams Create Expertise

Caring for the sickest PE patients is not simple. It takes expertise in multiple fields including imaging, intensive care, circulatory support, cardiac surgery and more. Also, medical decisions require finesse. A knowledgeable internist, hematologist or vascular medicine specialist can improve decision making.

By bringing together these various team members over time, we can create expertise. People can gain knowledge in the latest literature. But more importantly, team forming takes time and practice. A PERT can offer just that.

Pulmonary Embolism Response Team Members

The composition of PERT teams changes from one medical center to the other. In large, academic, medical centers, team members will usually represent many medical specialties from vascular medicine and hematology to interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery. But in smaller centers, the team is usually made of whoever wants to focus on pulmonary embolism. The ideal structure of a PERT is yet to be determined. But a team that fits its environment is probably a good place to start.

Is there Proof of Benefit?

While PERT make sense, it turns out proving benefit is not easy. In fact, the little data that is out there is negative. In fact, in parallel to lack of evidence for benefit, there is some evidence for more resource utilization. For instance, in a paper I published together with Eric Secemsky and others we showed mortality in a major PERT center to be rather identical to mortality from decades ago.

Still, an academic literature search will surely find numerous suggestions about structuring such teams and opinion pieces touting their benefits. Sometimes, irrelevant benefits (such as “door to procedure time”), while supporting the notion of efficacy, are conflated with real patient benefit. Of course, in reality, this may actually be a sign of unnecessary procedures.

Importantly, the horses are out of the barn. As a rule, there is a huge and vocal international following for the PERT movement. A massive body of physicians, often hospital medicine, pulmonary medicine and hematology specialists, who may not be so supportive, remain more silent.

Real Life Pulmonary Embolism Response Team Disadvantages

In real life, PERT may actually have some disadvantages.

Excess Resource Utilization

First, there may be excess resource utilization without tangible benefit. This resource utilization might happen at various stages of a patient’s journey. First, some patients might receive unnecessary testing such as thrombophilia testing. Next, patients may receive more in-patient consultations than needed, driving the price of care up. Then, after discharge, there may be duplicate follow-up, both by the primary care physician and also by various specialists who saw the patients in-house.

Some Patients Need Extra Care

Of course, some patients need this extra care. They will benefit from extra testing, more resources, and closer surveillance. For instance, high-risk PE patients or some patients with clot in transit. Also, being able to talk across specialties has clear benefits. For instance, if a PE patients suffers anticoagulation failure. But probably many patients who end up having such care would have done well without it, even from these potentially high-risk groups. Unfortunately, creating an efficient system that identifies only those patients who need the extra care is very hard.

False Expertise

Another potential disadvantage is false expertise. Team members may not be well versed in current literature, but still be forced to make decisions. Also, others in their medical centers will come to them for advice, whether they know what they are doing or not. It does not take much effort to find such false experts on panels in various conferences spouting falsehoods with confidence.

Improper Team Work

Finally, to truly benefit from the wisdom of a team, each team member should be given equal weight in decision making. But we all know that is not humans work. In groups, there are often more dominant figures than others. Also, team members might refrain from speaking up. For instance, because they are junior or because they want to maintain a good relationship with a colleague. These behavioral patterns can give the false impression that decisions have the backing of a team, while in reality they do not.